Original Airdate: November 25, 1984

Directed by Michael Gornick.

Written by Michael McDowell, Based on the story “The Word Processor of the Gods” by Stephen King.

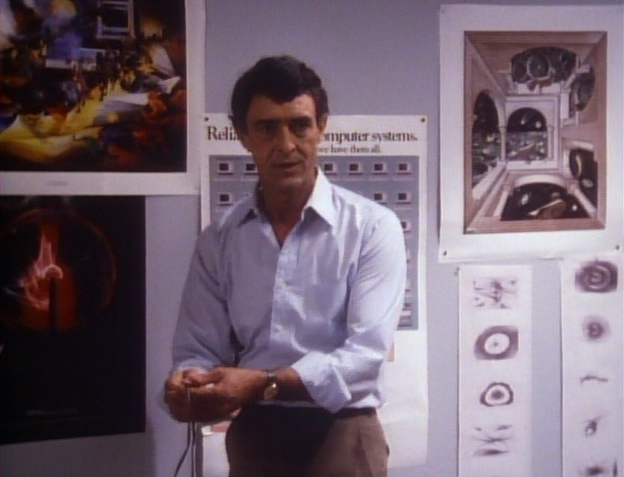

Starring Bruce Davison (Richard Hagstrom), Karen Shallo (Lina Hagstrom), Patrick Piccininni (Seth Hagstrom), William Cain (Tom Nordhoff), Jon Shear (Jonathan), Miranda Beeson (Belinda).

SYNOPSIS: Richard has just received a homemade word processor from his recently deceased nephew Jonathan, the victim of a car accident that also claimed the lives of his mother Belinda and drunkard father. Richard’s wife Lina derides him for his writerly ambitions, and his punk son Seth is too busy wailing on his guitar to pay him any mind. Not the best life, but Richard finds that the machine is here to fix that with whatever command he types on the keyboard.

CRITIQUE: Is there some unwritten rule that stipulates that all ambitious writers must be wed to total jerks? Richard’s wife has a complete lack of faith in her husband’s talents—even though he has published a novel—and sees the whole pursuit as a waste of time. It’s true that the vocation can be a very unfulfilling one, but I can’t help but notice that in almost all of the stories of this type the spouse of the struggling scribe must be the kind of “you’ll-never-really-amount-to-anything” bully that invariably sets up our protagonist for a “Well I’ll show them!” comeback.

|

| For some inexplicable reason, Mr. Nordhoff remembers he left bacon on the stove. |

This is another in a long line of wish-fulfillment stories that the series will present to us, but this is a rare case where our hero doesn’t come to regret his desires and actually gets what he wants, probably because he wears glasses. Poor vision is usually a solid “Get Out of Eternal Judgment” card. An intriguing spin occurs when we discover that Richard had loved the late Belinda and had felt a fatherly kinship with whiz kid nephew Jonathan. It adds some perspective to Richard’s desire and makes his plight more sympathetic to us: he only wanted what was in his reach, but he could never have it.

The episode also realizes one of man’s deepest inherent wishes, to be able to write the book of our lives and dictate an upturn in our fortunes by the mere click of a key or rub of a magic lamp. The rest of the segment operates under the same trajectory of events that we have come to expect from this type of drama: Richard gradually realizes the power of his enchanted totem, here represented by the “Execute” and “Delete” buttons on the keyboard, first experimenting on some random object (a framed picture of his wife) before making a legitimate wish to further glean its power (first for twelve Spanish gold doubloons and then for his son's disppearance) only to hurriedly issue a final plea to restore order as everything goes up in smoke. If you’ve read “The Monkey’s Paw,” you’ve seen this before.

There’s a touch of W. W. Jacobs in a bit where Richard answers the door after he’s zapped Seth into the ether to find a weeping Lina in funeral garb, her running mascara giving her the look of a revenant as she stumbles forward and accuses Richard of killing their son. This is just a fake-out, a nervous vision inspired by Richard’s guilt, but it does distract for a little while with its expressionistic blue lighting that recalls the vibrant hues of CREEPSHOW (1982). The lead-up to Seth’s deletion is also reminiscent of THE BODY SNATCHER (1945) when we hear the guitar’s shrieking cut off after the duct tape-bound machine has carried out its function.

|

| Rock all day. Every day. |

McDowell’s adaptation of the material carries over King's tone and content so completely that it almost appears that Gornick simply filmed the story, adding a few small filmic touches that allow it to play out a little better for the aural/visual medium. The faithfulness to King is both for better and worse as some of the author's hinky dialogue gets carried over; at the conclusion Richard asks the revived Jonathan to "delete [the word processor] from our lives." The episode takes the overly-sweet final note of the boys indulging in a cup of hot cocoa like a real family and gives it some emotional resonance with the heavenly image of the radiant Belinda waiting for them, silent but smiling. It’s enough to make you forget the formulaic journey it took for us to get here and ask “Wouldn’t it be nice?”

McDowell’s adaptation of the material carries over King's tone and content so completely that it almost appears that Gornick simply filmed the story, adding a few small filmic touches that allow it to play out a little better for the aural/visual medium. The faithfulness to King is both for better and worse as some of the author's hinky dialogue gets carried over; at the conclusion Richard asks the revived Jonathan to "delete [the word processor] from our lives." The episode takes the overly-sweet final note of the boys indulging in a cup of hot cocoa like a real family and gives it some emotional resonance with the heavenly image of the radiant Belinda waiting for them, silent but smiling. It’s enough to make you forget the formulaic journey it took for us to get here and ask “Wouldn’t it be nice?”"The Word Processor of the Gods" originally appeared in the January 1983 issue of Playboy, the magazine for shrimpy writers with fat wives fantasizing of better lives (and hotter women) everywhere. Pair with a cold Budweiser for optimium satisfaction.

“It’s always the wrong people who die, Mr. Hagstrom.”

***

Rating: 2 1/2 Lizzies

Coming Up: Christian Slater finds his grandpappy is restless in peace in "A Case of the Stubborns."